the crusades were fought for over 2 centuries to achieve what for the Muslims and Christians

A comprehensive business relationship of a compelling and controversial topic, whose bitter legacy resonates to this day.

During the last iv decades the Crusades accept become 1 of the almost dynamic areas of historical enquiry, which points to an increasing curiosity to understand and interpret these extraordinary events. What persuaded people in the Christian West to want to recapture Jerusalem? What impact did the success of the Get-go Crusade (1099) take on the Muslim, Christian and Jewish communities of the eastern Mediterranean? What was the issue of crusading on the people and institutions of western Europe? How did people tape the Crusades and, finally, what is their legacy?

Bookish debate moved forwards significantly during the 1980s, as discussion concerning the definition of a crusade gathered real steam. Agreement of the scope of the Crusades widened with a new recognition that crusading extended far beyond the original 11th-century expeditions to the Holy Country, both in terms of chronology and scope. That is, they took place long later the end of the Frankish concord on the East (1291) and continued downwards to the 16th century. With regards to their target, crusades were besides called against the Muslims of the Iberian peninsula, the pagan peoples of the Baltic region, the Mongols, political opponents of the Papacy and heretics (such as the Cathars or the Hussites). An credence of this framework, equally well every bit the axis of papal authorisation for such expeditions, is generally referred to as the 'pluralist' position.

Download our special issue on the history of the Crusades

The emergence of this interpretation energised the existing field and had the effect of drawing in a far greater number of scholars. Alongside this came a growing interest in re-evaluating the motives of crusaders, with some of the existing emphases on money being downplayed and the cliche of landless younger sons out for chance being laid to rest. Through the utilize of a broader range of evidence than ever before (peculiarly charters, that is sales or loans of lands and/or rights), a stress on contemporary religious impulses every bit the ascendant driver for, specially the First Crusade, came through. Even so the wider earth intruded on and so, in some means, stimulated this academic debate: the horrors of 9/11 and President George W. Bush's disastrous use of the word 'crusade' to describe the 'war on terror' fed the extremists' message of detest and the notion of a longer, wider conflict between Islam and the West, dating dorsum to the medieval period, became extremely prominent. In reality, of grade, such a simplistic view is deeply flawed merely information technology is a powerful shorthand for extremists of all persuasions (from Osama Bin Laden to Anders Breivik to ISIS) and certainly provided an impetus to report the legacy of the crusading age into the mod world, as we will see hither, calling on the all-encompassing online archive of History Today.

***

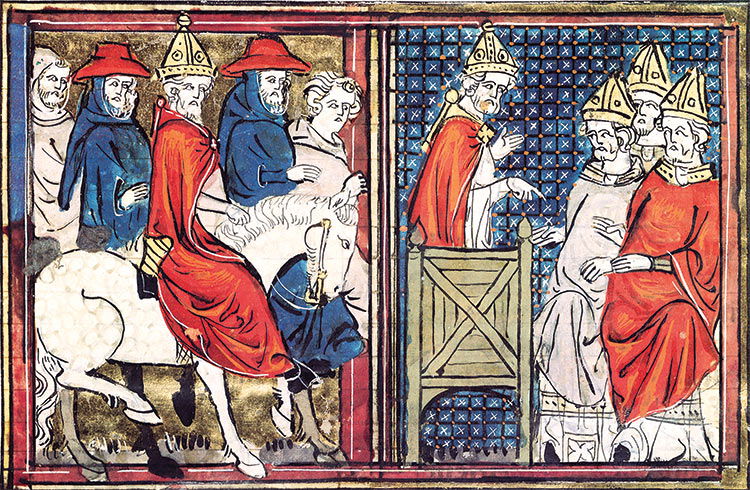

The First Cause was called in November 1095 by Pope Urban II at the boondocks of Clermont in central France. The pope made a proposal: 'Whoever for devotion alone, but not to gain honour or coin, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the Church of God tin substitute this journey for all penance.' This appeal was the combination of a number of contemporary trends along with the inspiration of Urban himself, who added particular innovations to the mix. For several decades Christians had been pushing back at Muslim lands on the edge of Europe, in the Iberian peninsula, for case, equally well every bit in Sicily. In some instances the Church had become involved in these events through the offer of limited spiritual rewards for participants.

Urban was responsible for the spiritual well-being of his flock and the crusade presented an opportunity for the sinful knights of western Europe to cease their countless in-fighting and exploitation of the weak (lay people and churchmen akin) and to make good their violent lives. Urban saw the entrada every bit a chance for knights to straight their energies towards what was seen equally a spiritually meritorious act, namely the recovery of the holy urban center of Jerusalem from Islam (the Muslims had taken Jerusalem in 637). In return for this they would, in effect, be forgiven those sins they had confessed. This, in turn, would save them from the prospect of eternal damnation in the fires of Hell, a fate repeatedly emphasised past the Church as the consequence of a sinful life. To find out more see Marcus Bull, who reveals the religious context of the campaign in his 1997 article.

Within an age of such intense religiosity the city of Jerusalem, as the place where Christ lived, walked and died, held a central role. When the aim of liberating Jerusalem was coupled to lurid (probably exaggerated) stories of the maltreatment of both the Levant's native Christians and western pilgrims, the want for vengeance, along with the opportunity for spiritual advancement, formed a hugely potent combination. Urban would exist looking after his flock and improving the spiritual status of western Europe, too. The fact that the papacy was engaged in a mighty struggle with the German emperor, Henry 4 (the Investiture Controversy), and that calling the crusade would heighten the pope'southward standing was an opportunity also good for Urban to miss.

A spark to this dry tinder came from another Christian forcefulness: the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Alexios I feared the advance of the Seljuk Turks towards his capital city of Constantinople. The Byzantines were Greek Orthodox Christians just, since 1054, had been in a state of schism with the Catholic Church. The launch of the crusade presented Urban with a chance to move closer to the Orthodox and to heal the rift.

The reaction to Urban's appeal was astounding and news of the trek rippled beyond much of the Latin West. Thousands saw this as a new way to accomplish conservancy and to avert the consequences of their sinful lives. Withal aspirations of honour, take chances, fiscal gain and, for a very small number, land (in the outcome, most of the First Crusaders returned home afterward the trek ended) may well have figured, also. While churchmen frowned upon worldly motives because they believed that such sinful aims would incur God's displeasure, many laymen had little difficulty in accommodating these aslope their religiosity. Thus Stephen of Blois, i of the senior men on the campaign, could write abode to his wife, Adela of Blois (daughter of William the Conquistador), that he had been given valuable gifts and honours by the emperor and that he at present had twice as much gold, silver and other riches as when he left the West. People of all social ranks (except kings) joined the Starting time Crusade, although an initial blitz of ill-disciplined zealots sparked an horrific outbreak of antisemitism, especially in the Rhineland, equally they sought to finance their trek by taking Jewish money and to assault a group perceived as the enemies of Christ in their own lands. These contingents, known as the 'Peoples' Crusade', caused real problems exterior Constantinople, before Alexios ushered them over the Bosporus and into Asia Minor, where the Seljuk Turks destroyed them.

Led by a series of senior nobles, the main armies gathered in Constantinople during 1096. Alexios had non expected such a huge number of westerners to appear on his doorstep but saw the chance to recover land lost to the Turks. Given the crusaders' need for food and transport, the emperor held the upper hand in this relationship, although this is not to say that he was anything other than cautious in dealing with the new arrivals, particularly in the aftermath of the trouble caused by the Peoples' Cause and the fact that the main armies included a large Norman Sicilian contingent, a group who had invaded Byzantine lands equally recently every bit 1081. Run across Peter Frankopan. Most of the crusade leaders swore oaths to Alexios, promising to hand over to him lands formerly held by the Byzantines in return for supplies, guides and luxury gifts.

***

In June 1097 the crusaders and the Greeks took i of the emperor's key objectives, the formidable walled city of Nicaea, 120 miles from Constantinople, although in the aftermath of the victory some writers reported Frankish discontent at the division of booty. The crusaders moved inland, heading across the Anatolian plain. A big Turkish army attacked the troops of Bohemond of Taranto about Dorylaeum. The crusaders were marching in split up contingents and this, plus the unfamiliar tactics of swift attacks past mounted horse archers, almost saw them defeated until the inflow of forces under Raymond of Toulouse and Godfrey of Bouillon saved the day. This hard-won victory proved an invaluable lesson for the Christians and, as the expedition went on, the military cohesion of the crusader ground forces grew and grew, making them an e'er more than effective force.

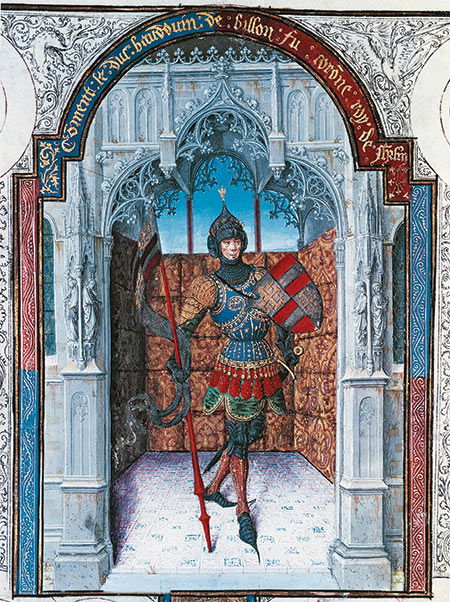

Over the next few months the army, under Count Baldwin of Boulogne, crossed Asia Small with some contingents taking the Cilician towns of Tarsus and Mamistra and others, heading via Cappadocia towards the eastern Christian lands of Edessa (biblical Rohais), where the largely Armenian population welcomed the crusaders. Local political disharmonize meant Baldwin was able to take power himself and thus, in 1098, the first so-called Crusader State, the County of Edessa, came into being.

By this fourth dimension the majority of the army had reached Antioch, today simply inside the southern Turkish border with Syria. This huge city had been a Roman settlement; to Christians it was significant as the place where saints Peter and Paul had lived and it was one of the five patriarchal seats of the Christian Church building. It was also important to the Byzantines, having been a major city in their empire every bit recently as 1084. The site was too big to surround properly but the crusaders did their best to squeeze the place into submission. Over the winter of 1097 conditions became extremely harsh, although the arrival of a Genoese fleet in the jump of 1098 provided some useful support. The stalemate was merely ended when Bohemond persuaded a local Christian to beguile 1 of the towers and on June 3rd, 1098 the crusaders broke into the city and captured it. Their victory was not complete, however, because the citadel, towering over the site, remained in Muslim easily, a problem compounded by the news that a large Muslim relief army was budgeted from Mosul. Lack of food and the loss of most of their horses (essential for the knights, of course) meant that morale was at rock bottom. Count Stephen of Blois, one of the most senior figures on the cause, along with a few other men, had recently deserted, assertive the expedition doomed. They met Emperor Alexios, who was bringing long-awaited reinforcements, and told him that the crusade was a hopeless crusade. Thus, in good faith, the Greek ruler turned back. In Antioch, meanwhile, the crusaders had been inspired by the 'discovery' of a relic of the Holy Lance, the spear that had pierced Christ's side equally he was on the cross. A vision told a cleric in Raymond of St Gilles' ground forces where to dig and, sure plenty, there the object was plant. Some regarded this as a bear upon convenient and too easy a boost to the continuing of the Provençal contingent, but to the masses information technology acted every bit a vital inspiration. A couple of weeks later, on June 28th, 1098, the crusaders gathered their concluding few hundred horses together, drew themselves into their now familiar boxing lines and charged the Muslim forces. With writers reporting the help of warrior saints in the sky, the crusaders triumphed and the citadel duly surrendered leaving them in full control of Antioch earlier the Muslim relief ground forces arrived.

***

In the aftermath of victory many of the exhausted Christians succumbed to disease, including Adhémar of Le Puy, the papal legate and spiritual leader of the campaign. The senior crusaders were bitterly divided. Bohemond wanted to stay and consolidate his concord on Antioch, arguing that since Alexios had not fulfilled his side of the bargain and so his oath to the Greeks was void and the conquest remained his. The bulk of the crusaders scorned this political squabbling because they wanted to reach Christ's tomb in Jerusalem and they compelled the army to head southwards. En route, they avoided major set-piece confrontations by making deals with individual towns and cities and they reached Jerusalem in June 1099. John France relates the capture of the urban center in his article from 1997.

Forces concentrated to the north and the s of the walled city and on July 15th, 1099 the troops of Godfrey of Bouillon managed to bring their siege towers shut enough to the walls to get across. Their fellow Christians burst into the urban center and over the side by side few days the identify was put to the sword in an outburst of religious cleansing and a release of tension afterwards years on the march. A terrible massacre saw many of the Muslim and Jewish defenders of the city slaughtered, although the oft-repeated phrase of 'wading upwards to their knees in claret' is an exaggeration, being a line from the apocalyptic Volume of Revelation (xiv:20) used to convey an impression of the scene rather than a existent description – a physical impossibility. The crusaders gave emotional thanks for their success as they reached their goal, the tomb of Christ in the Holy Sepulchre.

Download our special event on the history of the Crusades

Their victory was non withal bodacious. The vizier of Arab republic of egypt had viewed the crusaders' advance with a mixture of emotions. As the guardian of the Shi'ite caliphate in Cairo he had a profound dislike of the Sunni Muslims of Syria, but equally he did not want a new ability to institute itself in the region. His forces confronted the crusaders near Ascalon in August 1099 and, in spite of their numerical inferiority, the Christians triumphed and besides secured a substantial amount of booty. By this fourth dimension, having accomplished their aims, the vast majority of the exhausted crusaders were only too great to return to their homes and families. Some, of course, chose to remain in the Levant, resolved to guard Christ'southward patrimony and to ready upwards lordships and holdings for themselves. Fulcher of Chartres, a contemporary in the Levant, lamented that simply 300 knights stayed in the kingdom of Jerusalem; a tiny number to plant a permanent hold on the land.

***

Over the next decade, however, aided by the lack of existent opposition from the local Muslims and boosted past the arrival of a series of fleets from the W, the Christians began to accept control of the whole coastline and to create a series of viable states. The support of the Italian trading cities of Venice, Pisa and, peculiarly at this early stage, Genoa, was crucial. The motives of the Italians have often been questioned just in that location is disarming evidence to testify they were just as keen as any other contemporaries to capture Jerusalem, yet as trading centres they were determined to advance the cause of their dwelling metropolis, too. The writings of Caffaro of Genoa, a rare secular source from this period, show trivial difficulty in assimilating these motives. He went on pilgrimage to the River Jordan, attended Easter ceremonies in the Holy Sepulchre and historic the acquisition of riches. Italian sailors and troops helped capture the vital littoral ports (such as Acre, Caesarea and Jaffa), in return for which they were awarded generous trading privileges which, in turn, gave a vital boost to the economy as the Italians transported goods from the Muslim interior (especially spices) back to the Westward. Just as important was their function in bringing pilgrims to and from the Holy Country. Now that the holy places were in Christian hands, many thousands of westerners could visit the sites and, as they came under Latin control, religious communities flourished. Thus, the basic rationale backside the Crusades was fulfilled. In that location is a strong case for saying that the crusader states could not take been sustained were information technology not for the contribution of the Italians.

One interesting side-effect of the Showtime Cause (and a matter of immense involvement to scholars today) is the unprecedented burst of historical writing that emerged afterwards the capture of Jerusalem. This amazing episode inspired authors beyond the Christian West to write about these events in a way that nada in earlier medieval history had done. No longer had they to look back to the heroes of antiquity, because their own generation had provided men of comparable renown. This was an age of rising literacy and the creation and apportionment of cause texts was a big function of this movement. Numerous histories, plus oral storytelling, often in the class of Chansons de geste, popular inside the early flowerings of the chivalric age, celebrated the First Crusade. Historians have previously looked at these narratives to construct the framework of events but now many scholars are looking behind these texts to consider more than deeply the reasons why they were written, the dissimilar styles of writing, the use of classical and biblical motifs, the inter-relationships and the borrowings between the texts.

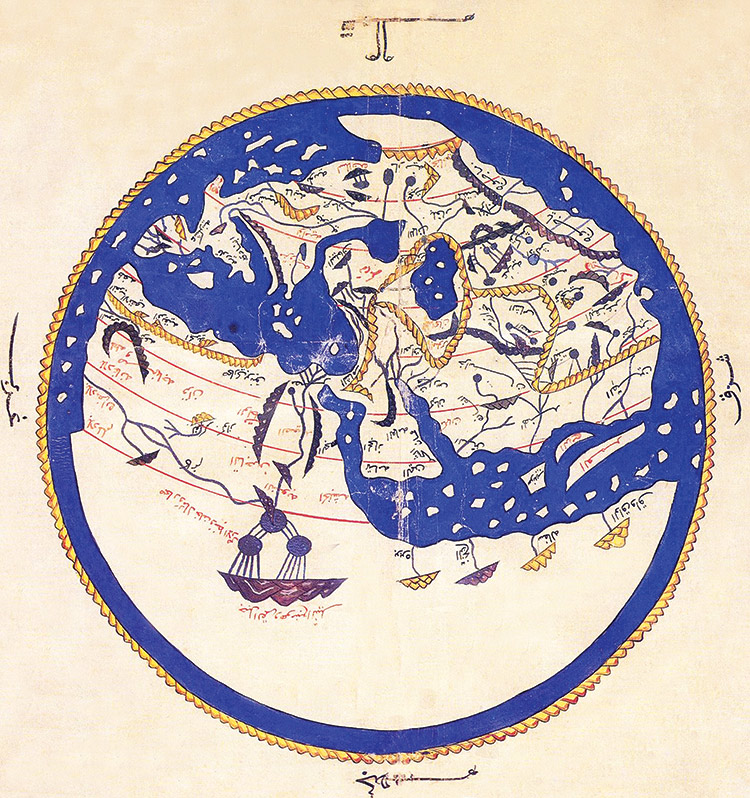

Another expanse to receive increasing attention is the reaction of the Muslim world. Information technology is now clear that when the First Crusade arrived the Muslims of the Virtually East were extremely divided, not just along the Sunni/Shi'ite fault line, but also, in the example of the quondam, amidst themselves. Robert Irwin draws attention to this in his 1997 article, also every bit considering the impact of the cause on the Muslims of the region. It was a fortunate coincidence that during the mid-1090s the death of senior leaders in the Seljuk world meant that the crusaders encountered opponents who were primarily concerned with their own political infighting rather than seeing the threat from outside. Given that the First Crusade was, self-evidently, a novel event, this was understandable. The lack of jihad spirit was too evident, equally lamented by as-Sulami, a Damascene preacher whose urging of the ruling classes to pull themselves together and fulfil their religious duty was largely ignored until the time of Nur advert-Din (1146-74) and Saladin onwards.

The Frankish settlers had to fit in to the complex cultural and religious blend of the Near East. Their numbers were so few that once they had captured places they very quickly needed to accommodate their behaviour from the militant holy war rhetoric of Pope Urban II to a more than businesslike stance of relative religious toleration, with truces and even occasional alliances with various Muslim neighbours. Had they oppressed the majority local population (and many Muslims and eastern Christians lived under Frankish rule), in that location would take been no-1 to farm the lands or to revenue enhancement and their economy would simply accept collapsed. Recent archaeological work by the Israeli scholar Ronnie Ellenblum has done much to testify that the Franks did not, every bit was previously believed, live solely in the cities, separated from the local populace. Local Christian communities ofttimes existed alongside them, sometimes fifty-fifty sharing churches.

The Frankish states of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem established themselves in the complex religious, political and cultural landscape of the Near Eastward. 1 of the early rulers of Jerusalem had married into native Armenian Christian dignity and thus Queen Melisende (1131-52) had a stiff interest in supporting the indigenous likewise as the Latin Church. The quirks of genetics, coupled with a loftier mortality charge per unit amidst male rulers, meant that women exerted greater power than previously supposed given the state of war-torn environment of the Latin East and prevailing religious attitudes towards women as weak temptresses. It even so needed a stiff personality to survive and, in the case of Melisende, that was certainly so, as Simon Sebag Montefiore recounts in a 2011 commodity, which also gives a sense of the city of Jerusalem during the 12th century, equally well as some gimmicky Muslim views of the Christian settlers.

The Franks were always brusque on manpower but were a dynamic group who developed innovative institutions, such as the Military Orders, to survive. The Orders were founded to help look after pilgrims; in the case of the Hospitallers, through healthcare; in that of the Templars, to baby-sit visitors on the road to the River Jordan. Presently both were fully-fledged religious institutions, whose members took the monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. It proved a popular concept and donations from admiring and grateful pilgrims meant that the Armed services Orders adult a major role as landowners, as the custodians of castles and as the commencement existent standing army in Christendom. They were independent of the control of the local rulers and could, at times, crusade trouble for the king or squabble with one another. The Templars and Hospitallers also held huge tracts of country beyond western Europe, which provided income for the fighting machine in the Levant, specially the construction of the castles that became and so vital to the Christian hold on the region.

***

In December 1144 Zengi, the Muslim ruler of Aleppo and Mosul, captured Edessa to marking the beginning major territorial setback for the Franks of the About Eastward. The news of this disaster prompted Pope Eugenius Three to issue an appeal for the Second Crusade (1145-49). Fortified by this powerful call to alive upwardly to the deeds of their first crusading forefathers, coupled with the inspiring rhetoric of (Saint) Bernard of Clairvaux, the rulers of France and Frg took the cross to mark the start of royal involvement in the Crusades. Christian rulers in Iberia joined with the Genoese in attacking the towns of Almeria in southern Spain (1147) and Tortosa in the north-east (1148); likewise the nobles of northern Federal republic of germany and the rulers of Denmark launched an trek against the heathen Wends of the Baltic shore around Stettin. While this was no thou plan of Pope Eugenius but rather a reaction to appeals sent to him, information technology shows the confidence in crusading at this time. In the event, this optimism proved deeply unfounded. A grouping of Anglo-Norman, Flemish and Rhineland crusaders captured Lisbon in 1147 and the other Iberian campaigns were too successful but the Baltic campaign achieved virtually nothing and the near prestigious expedition of all, that to the Holy Land, was a disaster, as Jonathan Phillips explains in his 2007 article. The two armies lacked subject, supplies and finance, and both were badly mauled by the Seljuk Turks every bit they crossed Asia Minor. And then, in conjunction with the Latin settlers, the crusaders laid siege to the most important Muslim urban center in Syria, Damascus. Still, after simply four days, fear of relief forces led by Zengi'southward son, Nur ad-Din, prompted an ignominious retreat. The crusaders blamed the Franks of the Well-nigh East for this failure, accusing them of accepting a pay-off to retreat. Any the truth in this, the defeat at Damascus certainly damaged crusade enthusiasm in the West and over the next three decades, in spite of increasingly elaborate and frantic appeals for help, there was no major crusade to the Holy Land.

To regard the Franks as entirely enfeebled would, even so, be a serious error. They captured Ascalon in 1153 to complete their control of the Levantine declension, an of import advance for the security of merchandise and pilgrim traffic in terms of reducing harassment by Muslim shipping. The following year, however, Nur advertizing-Din took power in Damascus to marking the first time that the cities had been joined with Aleppo under the rule of the same man during the crusader period, something that greatly increased the threat to the Franks. Nur ad-Din's considerable personal piety, his encouragement of madrasas (education colleges) and the composition of jihad poetry and texts extolling the virtues of Jerusalem created a bond between the religious and the ruling classes that had been conspicuously lacking since the crusaders arrived in the East. During the 1160s Nur ad-Din, interim as the champion of Sunni orthodoxy, seized control of Shi'ite Egypt, dramatically raising the strategic pressure on the Franks and at the aforementioned time enhancing the fiscal resources at his disposal through the fertility of the Nile Delta and the vital port of Alexandria.

This catamenia of the history of the Latin Eastward is related in detail by the most important historian of the age, William, Archbishop of Tyre, equally Peter Edbury describes. William was an immensely educated homo, who soon became embroiled in the bitter political struggles of the tardily 1170s and 1180s during the reign of the tragic figure of Rex Baldwin IV (1174-85), a youth afflicted by leprosy. The need to constitute his successor provided an opportunity for rival factions to emerge and to cause the Franks to expend much of their free energy on bickering with each other. That is not to say that they were unable to inflict serious harm on Nur ad-Din'south ambitious successor, Saladin, who from his base in Egypt, hoped to usurp his old master'south dynasty, draw the Muslim Virtually East together and to miscarry the Franks from Jerusalem. Norman Housely expertly relates this period in his 1987 article. In 1177, all the same, the Franks triumphed at the Battle of Montgisard, a victory that was widely reported in western Europe and did picayune to convince people of the settlers' very real need for aid. The construction in 1178 and 1179 of the large castle of Jacob's Ford, only a day's ride from Damascus, was some other ambitious gesture that required Saladin to destroy the place. Yet past 1187 the sultan had gathered a large, but fragile coalition of warriors from Egypt, Syria and Iraq that was sufficient to bring the Franks into the field and to inflict upon them a terrible defeat at Hattin on July quaternary. Inside months, Jerusalem savage and Saladin had recovered Islam's third most important urban center afterwards Mecca and Medina, an achievement that still echoes down the centuries.

***

News of the calamitous fall of Jerusalem sparked grief and outrage in the Westward. Pope Urban Three was said to have died of a heart set on at the news and his successor, Gregory VIII, issued an emotive cause entreatment and the rulers of Europe began to organise their forces. Frederick Barbarossa's German ground forces successfully defeated the Seljuk Turks in Asia Minor only for the emperor to drown crossing a river in southern Turkey. Presently afterwards many of the Germans died of sickness and Saladin escaped facing this formidable enemy. The Franks in the Levant had managed to cling onto the urban center of Tyre and and then besieged the most important port on the coast, Acre. This provided a target for western forces and it was here in the summer of 1190 that Philip Augustus and Richard the Lionheart landed. The siege had lasted almost ii years and the inflow of the two western kings and their troops gave the Christians the momentum they needed. The city surrendered and Saladin's prestige was badly dented. Philip shortly returned home and while Richard fabricated two attempts to march on Jerusalem, fears as to its long-term prospects after he left meant that the holy metropolis remained in Muslim hands. Thus the Third Crusade failed in its ultimate objective, although it did at least allow the Franks to recover a strip of lands along the declension to provide a springboard for future expeditions. For his office, Saladin had suffered a series of armed forces setbacks but, crucially, he had held onto Jerusalem for Islam.

The pontificate of Innocent III (1198-1216) saw some other phase in the expansion of crusading. Campaigns in the Baltic advanced further and the holy war in Iberia stepped forwards as well. In 1195 Muslims had crushed Christian forces at the Boxing of Alarcos, which, then before long afterwards the disaster at Hattin, seemed to testify God's deep displeasure with his people. By 1212, however, the rulers of Iberia managed to pull together to rout the Muslims at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa to seal a major step in the recovery of the peninsula. That said, the particular cultural, political and religious make-up of the region mean that it would be incorrect, as in the Holy Country, to characterise relations between religious groups as constant warfare, a situation outlined past Robert Burns and Paul Chevedden. In southern France, meanwhile, efforts to curb the Cathar heresy had failed and, in a bid to defeat this sinister threat to the Church in its own backyard, Innocent authorised a crusade to the area. Run into the piece by Richard Cavendish. Catharism was a dualist faith, admitting with a few links to mainstream Christian practise, merely information technology also had its own hierarchy and was intent upon replacing the existing elite. Years of warfare ensued as the crusaders, led by Simon de Monfort, sought to drive the Cathars out, only ultimately their roots in southern French society meant they could suffer and it was only the more pervasive techniques of the Inquisition, initiated in the 1240s, that succeeded where strength had failed.

The most infamous episode of the historic period was the Quaternary Crusade (1202-04) which saw another effort to recover Jerusalem end up sacking Constantinople, the greatest Christian city in the world. Jonathan Phillips describes this episode. The reasons for this were a combination of long-standing tensions between the Latin (Cosmic) Church and the Greek Orthodox; the demand for the crusaders to fulfil the terms of a wildly over-optimistic contract for transportation to the Levant with the Venetians and the offering to pay this off by a claimant to the Byzantine throne. This combination of circumstances brought the crusaders to the walls of Constantinople and when their young candidate was murdered and the locals turned definitively confronting them they attacked and stormed the city. At first Innocent was delighted that Constantinople was nether Latin authority but every bit he learned of the violence and looting that had accompanied the conquest he was horrified and castigated the crusaders for 'the perversion of their pilgrimage'.

1 consequence of 1204 was the cosmos of a series of Frankish States in Greece that, over time, as well needed support. Thus, in the grade of the 13th century, crusades were preached against these Christians, although by 1261 Constantinople itself was dorsum in Greek easily.

***

In spite of this serial of disasters, it is interesting to see that crusading remained an bonny concept, something made manifest past the virtually-legendary Children'southward Crusade of 1212. Inspired by divine visions, two groups of young peasants (best described as youths, rather than children) gathered around Cologne and near Chartres in the belief that their purity would ensure divine approving and enable them to recover the Holy Land. The German group crossed the Alps and some reached the port of Genoa, where the harsh realities of having no money or real hope of achieving anything was fabricated plain when they were refused passage to the East and the entire enterprise collapsed.

Thus, the early on 13th century was characterised by the variety of crusading. Holy war was proving a flexible and adaptable concept that immune the Church to direct force against its enemies on many fronts. The rationale of crusading, as a defensive act to protect Christians, could exist refined to utilise specifically to the Catholic Church building and thus when the papacy came into disharmonize with Emperor Frederick II over the command of southern Italy information technology eventually called a crusade confronting him. Frederick had already been excommunicated for failing to fulfil his promises to take part in the Fifth Cause. This expedition had achieved the original intention of the Fourth Crusade by invading Egypt but became bogged downward outside the port of Damietta earlier a poorly executed try to march on Cairo complanate. Frederick's attempts to make skillful this were frustrated by genuine sick health simply past this fourth dimension the papacy had lost patience with him. Recovered, Frederick went to the Holy Land as, by this time, rex of Jerusalem (by wedlock to the heiress to the throne) where – irony of ironies – as an anathematize, he negotiated the peaceful restoration of Jerusalem to the Christians. His diplomatic skills (he spoke Arabic), the danger posed by his considerable resource likewise as the divisions in the Muslim earth in the decades later on Saladin's death, enabled him to accomplish this. A brief period of amend relations between pope and emperor followed, only by 1245 the curia described him as a heretic and authorised the preaching of a crusade against him.

Aside from the plethora of crusading expeditions that took place over the centuries, nosotros should besides remember that the launch of such campaigns had a profound bear on on the lands and people from whence they came, something covered by Christopher Tyerman. Crusading required substantial levels of financial support and this, over time, saw the emergence of national taxes to back up such efforts, as well as efforts to raise coin from within the Church itself. The absence of a large number of senior nobles and churchmen could touch the political balance of an area, with opportunities for women to act as regents or for unscrupulous neighbours to defy ecclesiastical legislation and to try to take the lands of absent crusaders. The decease or disappearance of a crusader, be they a minor figure or an emperor, obviously carried deep personal tragedy for those they had left behind, merely might also precipitate instability and alter.

The previous year, Jerusalem had fallen back into Muslim hands and this was the principal prompt for what turned out to be the greatest crusade expedition of the century (known every bit the Seventh Crusade) led by Rex (later Saint) Louis 9 of France. Simon Lloyd outlines Louis'southward crusading career. Well financed and advisedly prepared and with an early victory at Damietta, this campaign appeared to be set fair only for a reckless charge by Louis's blood brother at the Battle of Mansourah to weaken the crusaders' forces. This, coupled with hardening Muslim resistance, brought the trek to a halt and, starving and ill, they were forced to give up. Louis remained in the Holy Land for a further four years – a sign of his guilt at the failure of the campaign, but also a remarkable delivery for a European monarch to be absent-minded from his dwelling house for a total of six years – trying to bolster the defences of the Latin kingdom. By this fourth dimension, with the Latins largely confined to the coastal strip the settlers relied more and more on massive fortifications and it was during the 13th century that mighty castles such as Krak des Chevaliers, Saphet and Chastel Pelerin, too as the immense urban fortifications of Acre, took shape.

***

By this phase the political complexion of the Centre East was changing. The Mongol invaders added another dimension to the struggle as they conquered much of the Muslim world to the East; they had also briefly threatened Eastern Europe with brutal incursions in 1240-41 (which also prompted a crusade appeal). Saladin'due south successors were displaced past the Mamluks, the former slave-soldiers, whose figurehead, the sultan Baibars, was a ferocious exponent of holy war and did much to bring the crusader states to their knees over the next two decades. James Waterson describes their advance. Bouts of in-fighting among the Frankish dignity, further complicated by the involvement of the Italian trading cities and the Military Orders served to further weaken the Latin States and finally, in 1291, the Sultan al-Ashraf smashed into the city of Acre to stop the Christian concord on the Holy Land.

Some historians used to regard this equally the end of the crusades but, as noted in a higher place, since the 1980s there has been a broad recognition that this was not the example, not to the lowest degree because of the serial of plans fabricated to try to recover the Holy Land during the 14th century. Elsewhere crusading was withal a powerful idea, not to the lowest degree in northern Europe, where the Teutonic Knights (originally founded in the Holy Land) had transferred their interests and where they had created what was effectively an democratic state. By the early on 15th century, however, their enemies in the region were starting to Christianise anyway and thus it became impossible to justify connected conflict in terms of holy war. The success of Las Navas de Tolosa had effectively pinned the Muslims downward to the very south of the Iberian peninsula, but information technology took until 1492 when Ferdinand and Isabella brought the full strength of the Spanish crown to bear on Granada that the reconquest was completed. Plans to recover the Holy Land had not entirely died out and in a spirit of religious devotion, Christopher Columbus set out the same year hoping to observe a route to the Indies that would enable him to reach Jerusalem from the East.

The 14th century began with loftier drama: the arrest and imprisonment of the Knights Templar on charges of heresy, a story related by Helen Nicholson. A combination of lax religious observance and their failure to protect the Holy State had made them vulnerable. This uncomfortable situation, coupled with the French crown owing them huge sums of money (the Templars had emerged as a powerful banking establishment) meant that the manipulative and relentless Philip IV of French republic could pressure Pope Clement V into suppressing the Order in 1312 and one of the dandy institutions of the medieval age was terminated.

Crusading within Europe itself had continued to mutate, as well. The papacy had issued crusading indulgences on many occasions during its own struggles against both political enemies and against heretical groups such as the Hussites of Bohemia. The principal threat to Christendom by this time, however, was from the Ottoman Turks, who, equally Judith Herrin relates, captured Constantinople in 1453. Numerous efforts were fabricated to draw together the leaders of the Latin West, only the growing power of nation states and their increasingly engrained conflicts, exemplified by the Hundred Years' War, meant that there was little appetite for the kind of Europe-wide response that had been seen in 1187, for example. Nigel Saul outlines this period of crusading history in his article.

Sure dynasties such as the dukes of Burgundy, were enthusiastic about the idea of crusading and a couple of reasonably-sized expeditions took place, although the Burgundians and the Hungarians were thrashed at Nicopolis in Bulgaria in 1396. By the middle of the 15th century the Ottomans had already twice besieged Constantinople and in 1453 Sultan Mehmet II brought forwards an immense army to achieve his aim. Last-minute appeals to the W brought insufficient aid and the city fell in May. The Emperor Charles V invoked the crusading spirit in his defence of Vienna in 1529, although this struggle resembled more of an imperial fight rather than a holy war. Crusading had near run its course; people had go increasingly contemptuous about the Church building'southward auction of indulgences. The advance of the Reformation was another obvious accident to the idea, with crusading existence viewed as a manipulative and coin-making device of the Catholic Church building. By the late 16th century the terminal existent vestiges of the movement could be seen; the Spanish Armada of 1588 benefitted from crusade indulgences, while the Knights Hospitaller, who had first ruled Rhodes from 1306 to 1522 before making their base of operations on Republic of malta, inspired a remarkable victory over an Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Jonathan Riley-Smith relates the knights' story. The Hospitallers of Malta had also survived a huge Turkish siege in 1480 and their existence served equally a long-lasting relic of the original crusading conflict until Napoleon Bonaparte extinguished their rule of the island in 1798.

***

Crusading survived in the retentiveness and the imagination of the peoples of western Europe and the Middle East. In the erstwhile, it regained contour through the romantic literature of writers such every bit Sir Walter Scott and, equally lands in the Eye East fell to the imperialist empires of the age, the French, in particular, chose to draw links with their crusading past. The word became a autograph for a cause with moral right, be it in a non-war machine context, such as a crusade confronting drink, or in the horrors of the Kickoff Globe War. Full general Franco'due south ties with the Cosmic Church in Espana invoked crusading ideology in perhaps the closest modernistic incarnation of the idea and information technology remains a word in mutual usage today.

Download our special issue on the history of the Crusades

In the Muslim earth, the retentivity of the Crusades faded, although did not disappear, from view and Saladin continued to be a figure held out as an exemplar of a great ruler. In the context of the 19th century, the Europeans' invocation of the past congenital upon this existing memory and meant that the image of hostile, aggressive westerners seeking to conquer Muslim or Arab lands became extremely potent for Islamists and Arab Nationalist leaders alike, and Saladin, as the human who recaptured Jerusalem, stands as the man to aspire to. Articles past Jonathan Phillips and Umej Bhatia comprehend the memory and the legacy of the crusades to bring the story down to modern times.

Jonathan Phillips is Professor of Crusading History at Royal Holloway University of London and the author of Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades (Vintage, 2010).

Source: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/crusades-complete-history

0 Response to "the crusades were fought for over 2 centuries to achieve what for the Muslims and Christians"

Post a Comment